If we instead do our editing on a calibrated display, we can at least mitigate one half of the contribution to inaccuracies, making it much more likely that a photo at least looks closer to your original intention across different devices. By editing and viewing on two uncalibrated devices, you double count the effects of both inaccuracies, potentially accentuating any differences from what your original editing intention was. The photo that they see now has two contributing yellow shifts in color that are affecting your original intention: one from your edit on an uncalibrated monitor and one from theirs.

Now imagine that you share this photo with a friend whose uncalibrated display is slightly more yellow than standard. You edit your photos according to what you see and as a result your photo is unknowingly edited slightly more yellow to compensate for the bluish tint.

You don’t know this because you don’t have a calibrated display with which to compare it. Here’s a simplified example of how display calibration affects images across devices: Imagine that your uncalibrated display is too bluish relative to what a calibrated display should look like. Then, when you share that photo edit to another device, deviations in that device will further affect how the colors appear. If you edit a photo on an uncalibrated display, any deviations from those standards will affect your editing slightly. This problem is becoming less common with improvements in display hardware technology. As a display ages, its colors can start to shift out of its original specification. Even if a display was calibrated to a standard at the factory, displays can actually “wear in” over time. Many manufacturers don’t perform individual calibration on their displays before selling them to customers and so certain variations in manufacturing or hardware choices can create variations in how one display shows any given color relative to another. Regardless of what a display is supposedly capable of displaying, or what gamut it was built to display, there is still the issue of calibration. You can read more about color gamuts here. The 2020 M1 Macbook Pro, for example, is advertised to be able to display 100% of the DCI-P3 color gamut. Sometimes display manufacturers will even advertise how well a display can show colors from one of these standard color gamuts such as DCI-P3, Adobe RBG or sRGB. Most manufacturers at least build their display hardware to try to hit the targets established by those standard color gamuts. At the very least, display calibration is the best assurance that your work will be displayed as close to your artistic intention as possible.ĭevice displays are built around a few common standard color gamuts that define the range of colors that a display should be capable of showing.

#Displaycal spyder pro 2 password professional#

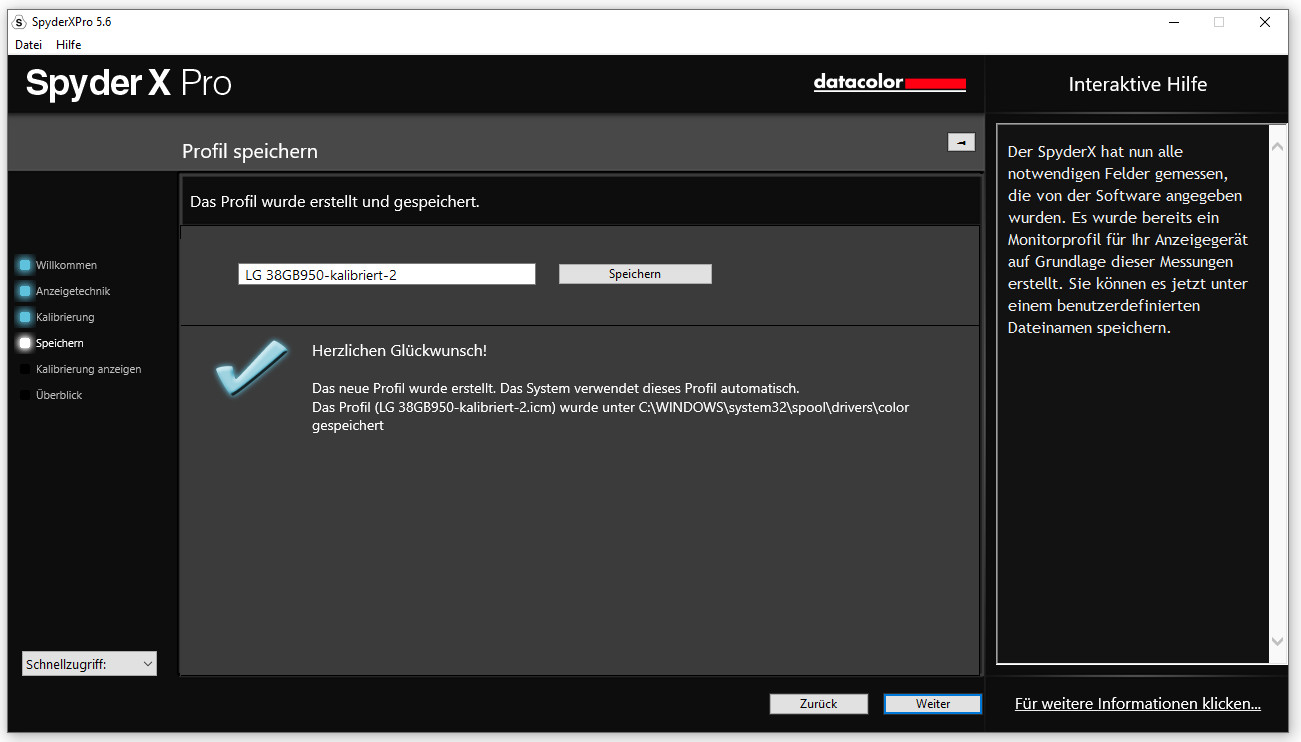

But if you do photography professionally or work on any other form of professional visual media, or if you prioritize the sharing of your work digitally or in print, calibrating your display may be essential. If you never share your photos, never print, and don’t use your photography in a professional setting, you don’t need to calibrate your display. Let me start by saying that calibration is not always necessary. The first step in trying to mitigate dramatic differences in photo colors across devices is calibration with a tool like the SpyderX Pro. With the plethora of devices that we have access to every day, if your primary photo editing display is uncalibrated, it’s likely that your personal photography collection looks slightly different when viewed on your display than when viewed on your phone and different from what your friend would see when you share your photos with them. In this review, we take a look at Datacolor’s SpyderX Pro Colorimeter display calibration tool.ĭisplay calibration is one of those things that’s too often forgotten or ignored in the realm of digital photography.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)